INTRODUCTION

In the last two blogs (here and here), we looked

at (in general) an article USA Today published entitled “The 18 worst product flops of all time.” These

flops included:

1. Edsel

by Ford Motor Co.

2. Touch

of Yogurt Shampoo by Bristol-Myers Squibb

3. Apple

Lisa by Apple

4. New

Coke by Coca-Cola

5.

Premier smokeless cigarettes by RJ Reynolds

6.

Maxwell House Brewed Coffee by Philip Morris Companies

7. Harley

Davidson perfume by Harley Davidson Motor Co.

8. Coors

Rocky Mountain Sparkling Water by Adolph Coors Co.

9.

Crystal Pepsi by Pepsico

10. The

Newton MessagePad by Apple

11.

Persil Power by Unilever

12. Arch

Deluxe by McDonald’s

13.

Breakfast Mates by the Kellogg Co.

14. WOW!

Chips by Pepsico

15. Hot

Wheels and Barbie computers by Mattel

16. EZ

Squirt (colored) Ketchup by Heinz

17.

TouchPad by HP

18.

Google Glass by Google

In this blog we will focus on only one of these flops:

Crystal Pepsi (#9).

LEARNINGS FROM CRYSTAL PEPSI

The major innovation for Crystal Pepsi (introduced in 1992),

was that the color was taken out of the cola to make it clear. The novelty of

drinking clear cola succeeded for a short period, but once the fad ended, sales

vaporized. What went wrong?

Learning #1: Just

Because You Can, Doesn’t Mean You Should

First of all, we need to understand that not everything new

and different is desirable. Just because an engineer can make something happen

doesn’t mean it should be done (no matter how much it would please the

engineer). Being able to take the color out of a cola might be a cool magic trick,

but where is the lasting benefit to the consumer?

Does taking out the color:

- Improve the taste? No.

- Improve the drinkability? No.

- Improve the formula? No.

- Lower the Price? No.

About the only lasting

benefit of Crystal Pepsi was that the caffeine was taken out. But Pepsi already

had caffeine free versions (since 1982), and you don’t need to take the color

out to take the caffeine out. So this really wasn’t much of a lasting benefit…just

a novelty.

I remember when digital

wristwatches first came out. Because they were digital, it was possible to

engineer them to do all sorts of things that the old analog watches couldn’t

do. Therefore, many had a buch of additional functions added, like stopwatch,

24 hour military time, etc. They fell victim to to adding features, just

because they could.

The problem was that the

designers only put a couple of buttons on the watch, making it almost

impossible to figure out what combination of button pressings were needed to

make the functions work. Worse yet, all that confusion also made it nearly

impossible to figure out how to set the watch for the correct time.

It was like the old VCR

players that always blinked "12:00" because nobody could figure out how to set the

timer. You could tolerate that on a VCR, because the video tapes could still

run without a working clock display. But a watch without a working clock

display is worthless. The manufacturers would have been better off putting in

fewer features so that the primary function—telling time—would have been

easier.

In Today’s digital era, the

temptation to do more innovation than necessary is probably greater than ever

before. You can alter the code to make digital products do almost anything. The

only limit is your imagination.

However, instead of using

your imagination as the limit, you should use practicality as your limit. If

the added feature gets in the way, confuses the customer, or does not provide

lasting/desired benefits, don’t do it. Tell the engineers to back off.

Just as the trick of taking

the color out of cola did not lead to success, many computer engineering tricks

may not lead to success, either.

Lesson #2: Image Works Both Ways

An innovation can improve the

image of a brand. It can make a brand appear more up-to-date, cooler, more

visionary, more desirable. Apple has used the innovations of the iPod, the

iPhone and the iPad to enhance its image in this way.

Unfortunately, some “innovations”

work on image in the opposite direction. Inappropriate innovations can make a

brand appear out-of-touch, silly, or incompotent. Taking the color out of cola

was a negative image producer. The so-called benefit was silly. Nobody was

aking for it (out of touch). Will I appear out-of-touch and silly if I drink

Crystal Pepsi?

Other potential negative

image factors in Crystal Pepsi:

- A clear cola appears less potent than a colored cola. Who wants a perceived diluted cola?

- What was done to take out the color? Were harsh chemicals used or added? Did they put bleach in the cola? Clear colas may be more dangerous to drink.

- Was the core formula changed? Failure #2 was New Coke, where Coke fans were outraged because the traditional Coke formula was changed. Couldn’t the same outrage occur here?

Innovations can create many undesired secondary consequences

which outweigh the slight benefits of poor innovations. Be sure to look for

these undesired secondary consequences before introducing the product.

Lesson #3: Hidden

Innovations Rarely Inspire

The whole trick of Crystal Pepsi was in seeing the color

taken out of the cola. Unfortunately, most colas are sold in cans and are

usually consumed right from the can. You cannot see the “clearness” of the cola

inside the can. What good is a benefit you never see or cannot discern during

consumption?

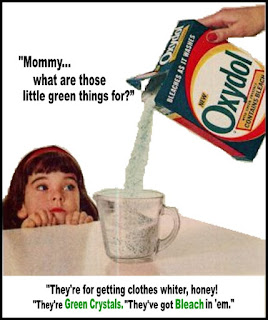

If you innovate, make sure the innovation is visible and

discernable. Oxydol detergent had the benefit of bleach already inside the

detergent. However, you couldn’t see the bleach, so consumers couldn’t feel the

benefit. Then Proctor & Gamble put little green crystals in Oxydol and told

people that the crystals were “proof” that Oxydol was different, and the

difference was bleach. After that, Oxydol became the #1 detergent in America

(until Proctor & Gamble decided to make Tide #1).

If you innovate, make sure the innovation is visible and

discernable. Oxydol detergent had the benefit of bleach already inside the

detergent. However, you couldn’t see the bleach, so consumers couldn’t feel the

benefit. Then Proctor & Gamble put little green crystals in Oxydol and told

people that the crystals were “proof” that Oxydol was different, and the

difference was bleach. After that, Oxydol became the #1 detergent in America

(until Proctor & Gamble decided to make Tide #1).

So, if you bother to innovate, make sure the customer knows

and provide some sort of visual confirmation to remind them of the innovation. Intel

was hidden inside computers and not getting much credit for their innovations.

So Intel made computer manufacturers put stickers on the outside of the

computer to let people know that there was Intel inside that computer. This

greatly improved the image benefits from Intel innovations.

SUMMARY

Crystal Pepsi teaches us that:

- Just because an innovation is possible does not mean that it is desirable;

- Poor innovations can damage a brand image at least as much as a good innovation can improve an image.

- To get the full impact of an innovation, it must be obvious to the consumer.