THE STORY

John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) was considered to be the best

composer and conductor of American marches who ever lived. His nickname was the

“American March King.”

When I was in college, I heard a story about a time when Sousa

had visited my college. He supposedly told the heads of the college that he

thought our college fight song was one of the best marches he had ever heard.

That made me feel proud.

However, now that I am older, I have heard many additional stories

about Sousa. As it turns out, John Philip Sousa visited a lot of colleges over his

lifetime. And each college tells a similar story about how Sousa told them that

their college fight song was one of the best he had ever heard.

Suddenly, Sousa’s stated opinion of my alma mater’s fight

song seems a lot more meaningless.

THE

ANALOGY

Strategists talk a lot about how companies should try to please their customer. But you hear far less about how customers often try to please the company…and this is a bad thing. Sousa is a perfect example of this phenomenon.

Strategists talk a lot about how companies should try to please their customer. But you hear far less about how customers often try to please the company…and this is a bad thing. Sousa is a perfect example of this phenomenon.

Think of the college as being like a company and their fight

song is their product. Sousa is the customer. In an attempt to try to please

all of the “companies” Sousa tells them all that he loves their “product” (the

fight song). So, in his attempt to please all of the “companies,” Sousa’s

opinion of their “product” becomes worthless.

Customers in today’s world are often giving as worthless an

opinion to companies as Sousa did to colleges—all in an attempt to please (not

offend) the company. This desire to be nice and no-offensive results in

consumer opinions which are as worthless as Sousa’s.

Many companies today use customer opinion surveys as a Key

Performance indicator (KPI) to judge their strategic success. Unfortunately, there

is often a Sousa-like bias in the customer to please the company and give

opinions which turn out to be meaningless. KPIs with meaningless data can be

very dangerous.

The principle here is that even though it is important to please the customer, don’t judge your success by asking customers if they were pleased. There is too much bias in the desire of many customers to please companies, making answers to those types of questions worthless.

One example which comes to mind are the quick auto oil

change companies. After you get your car’s oil changed, they send out a survey

to ask you if you were pleased with the service. This sounds reasonable until

one digs deeper.

As it turns out, many of the mechanics will tell their

customers about the survey they are about to receive. Then the mechanic tells them

that if they rate him with anything lower than a perfect score, the mechanic will

get no credit towards his performance bonus. Many customers don’t want to keep

their mechanic from getting a bonus and besides, who wants to return to a

mechanic who is upset at them for giving him a low score? You want your

mechanic to like you. So all of the sudden, almost all the mechanics are

getting superior grades (the Sousa phenomenon—worthless information).

To remedy the situation, on a recent oil change survey I saw

a new question asking if the mechanic told you in advance how your ranking

would affect him. I guess that was put in there to “weed out” some of the bias.

Unfortunately, just putting that question in the survey creates more of that

same bias. Who wants to get their mechanic in trouble for talking about the scores?

Preference is Better than Opinion

One way to get around opinion bias is to stop asking people’s

opinion about your product. For example, you could instead ask about

preferences. Using our analogy, that would be like instead of asking Sousa

about his opinion of your fight song, you would ask him to rank order the top

25 fight songs from favorite to least favorite. Sousa may still like them all,

but at least now you will know which ones he likes more.

Knowing customer preference (compared to numerous options) is

more important than opinion about a single product, because we don’t always buy

what we like, but are more likely to buy what we prefer.

I might like nearly all cars, but I don’t buy nearly all

cars. I am more likely to buy the car I prefer. Therefore preference among

choices is a better indicator of future success than mere opinion on a single

item.

Behavior is Better than Preference

But even here biases can creep in to distort the results. In

a desire to please the company, I might rank it higher in preference than I

should. Therefore, an even better question is to ask about past behavior. For

example, I could have asked Sousa how many times he listened to each of the

college fight songs in the past two years. Past behavior is less prone to bias.

Looking at what Sousa actually listens to is probably a better indicator of

what he actually likes than asking his opinion.

I would have far more confidence in a KPI measuring behavior

than one that measures opinion or preference.

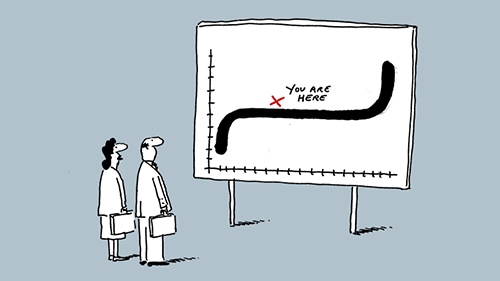

KPIs are a key part of strategy. Choosing a KPI that gives inaccurate or distorted information can be very dangerous. KPIs based on asking customers if they like you is one such dangerous KPI. It is better to ask for preferences against competition. Better yet, just ask about past behavior.

This problem is even worse if you are asking customers about new concepts or products for which they have to prior experience. As Steve Jobs of Apple used to say: “You can't just ask customers what they want and then try to give that to them. By the time you get it built, they'll want something new.” And when commenting on what kind of consumer research Apple did for the iPad, Jobs said, “None. It is not the consumers’ job to know what they want.” In other words, KPIs on future concepts should steer clear of consumer opinion even more than others. When it came to the future, Jobs marched to the tune of the future, not to the obsolete marches still in the heads of the customers.